What is intelligent speed assist?

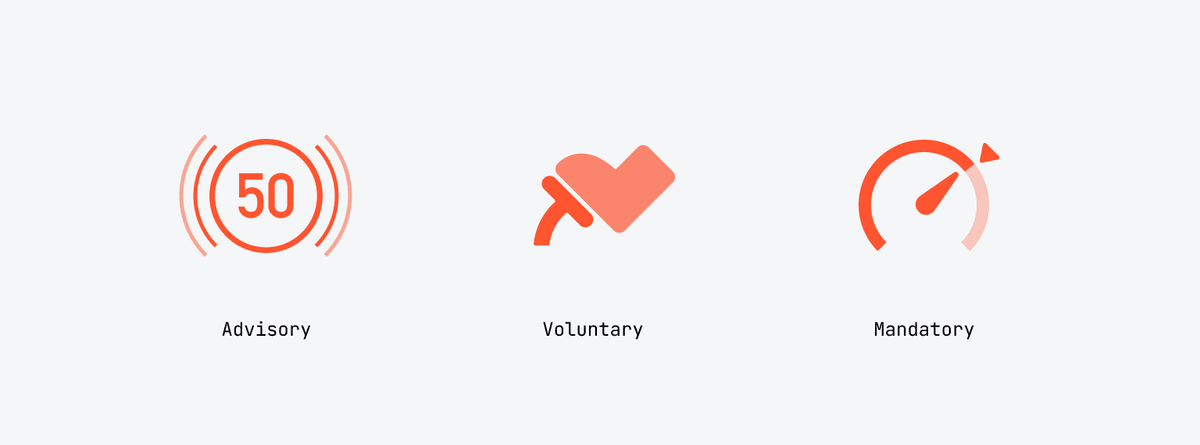

The speed limit warnings are part of a system called Intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA). Any system inside a vehicle that ensures that a driver does not exceed the speed limit is called ISA. There are three different types:

- Advisory ISA — The car informs drivers when they are speeding. For example, when a driver exceeds the speed limit, a visual or auditory signal is communicated to the driver.

- Voluntary ISA — The car will take a more active role in preventing speeding but the driver can override it. For example, if the speed limit is exceeded, the driver needs more force to press the gas pedal.

- Mandatory ISA — The car will prevent drivers from speeding. For example, the power to the engine is cut when the driver starts exceeding the speed limit.

Why do new cars have this?

The EU has passed a new regulation stating that every new passenger car on sale in the EU from July 2024 needs to have some form of ISA. According to the EU's press release, the objective is to protect Europeans against traffic accidents, poor air quality, and climate change, empower them with new mobility solutions that match their changing needs, and defend the competitiveness of European industry.

The main reason is of course safety. The European Road Safety Observatory reports that an estimated 10 to 15% of all road crashes and 30% of all fatal accidents are the direct result of speeding. The percentage of accidents where speed was one of the contributing factors is even higher.

Even though most new cars use an auditory signal, the EU actually doesn't require this, but offers carmakers four different implementations:

- Cascaded acoustic warning (Advisory ISA)

- Cascaded vibrating warning (Advisory ISA)

- Haptic feedback through the acceleration pedal (Voluntary ISA)

- Speed control function (Mandatory ISA)

For the first two cases, the car must first show a flashing speed limit indicator before the acoustic or vibrating warnings occur. The duration depends on the excess speed and can range from 3 to 6 seconds. The system can be overridden by the driver and turned off. But it must be turned on by default every time the vehicle is restarted. Even though I'm focusing on the EU, in many other countries, some form of ISA has already been implemented or is likely to be in the coming years.

What is the problem?

From a regulatory perspective, ISA sounds like a great technology. How could you be against trying to reduce traffic fatalities? Just stick to the speed limit and there are no problems, right? However, from a practical perspective, the EU's regulation raises a few concerns.

Having driven cars from a few different brands with this new ISA, I am surprized by how invasive it is. The system is sensitive, sending alerts when only barely exceeding the speed limit. Additionally, it often gets the speed limit wrong. It relies on a mix of GPS and camera data that often isn't accurate (yet) in most countries. This would be tolerable if it wasn't for the fact that an auditory signal is incredibly annoying.

These frequent beeps come in addition to auditory warnings for lane departure, driver drowsiness, eye gaze, following distance, and more. It was already difficult for drivers to understand the different assistance systems and what they do, and it is even more difficult now.

One could put part of the blame on the carmaker. After all, the EU offers four different implementations, not just an auditory one. However, voluntary and mandatory ISAs, like increasing the resistance on the throttle pedal, are intrusive methods with no public support and serious human factors considerations that first need to be researched properly. For example, what happens when a driver overrides the system by flooring the gas pedal and in doing so causes an accident?

So that leaves only two options — an auditory or a haptic signal. Most carmakers will therefore choose an auditory signal because it doesn't require any changes to the vehicle architecture. Fitting vibrating motors to seats is expensive, and probably no less annoying than a beep.

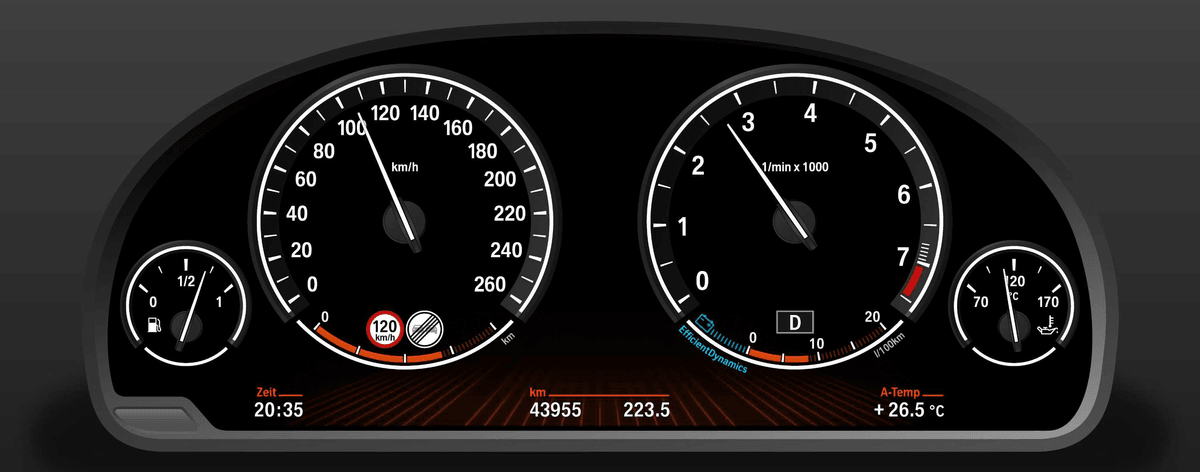

Interestingly, even before the regulation went into effect, most new cars already had Intelligent Speed Assistance in the form of a visual indicator. Euro NCAP made it part of its safety evaluation to include a speed limit indicator with a visual warning if you go over the limit. And therefore, it is part of the functional safety requirements of most carmakers.

Given that most cars already have visual indicators, why did the EU decide on its current regulation given that it is so intrusive and annoying? Does ISA work? And is an auditory warning more effective than a visual indicator? Let's dive into this.

Why do people speed?

When we think of speeding, we often assume bad intent. And even though speeding can be deliberate, more often there are subconscious reasons. For example, false risk perception, task difficulty, feel of the road, visibility conditions, and visual range.

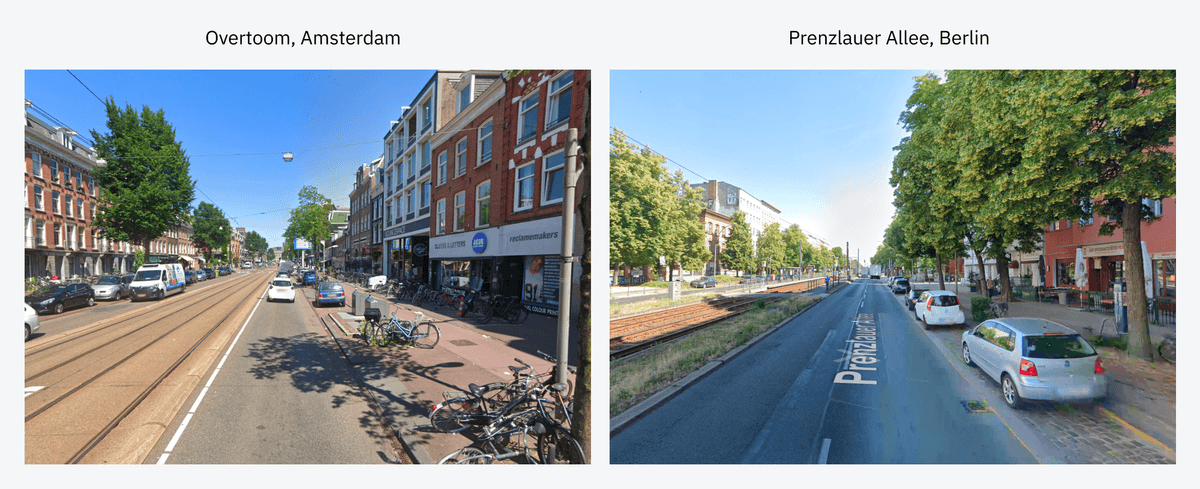

In a previous article about cognitive load, I explained the phenomenon of drivers having a subconscious preferred speed that they will naturally resort to. This depends a lot on outside factors like road design — the width, curvature, shoulder width, and design of the central divider impact the perceived speed. Drivers not paying attention on a wide road are more likely to speed than on a narrow one even though they don't intend to exceed the speed limit.

I witness a great example of this every day when comparing Berlin, where I am currently living, to Amsterdam, where I used to live. Even though both cities have roads with the same speed limits, drivers in Berlin drive much faster. German traffic engineers consider drivers to be rational agents who follow rules. Therefore, if there is a road where many drivers speed, the solution is to place more speed limit signs. Contrary to this input-based design of German infrastructure, the Netherlands resorts more to output-based design. When there is a road where drivers consistently speed, Dutch traffic engineers adjust the design of the road so that drivers subconsciously drive slower. The best way to do this is to narrow the road which makes it seem like you are driving faster than you actually are.

Even though infrastructure design reduces the frequency of speeding, it doesn't stop it completely. Dutch roads are safer than German ones, but there are still 6,5 million yearly traffic fines related to speeding in the Netherlands.

There is much debate on the effectiveness of road design compared to in-vehicle systems on speeding but the consensus is that it should be a mix of both. This is why the EU is looking at ISA as a way to reduce speeding. So does it work?

What does the research say?

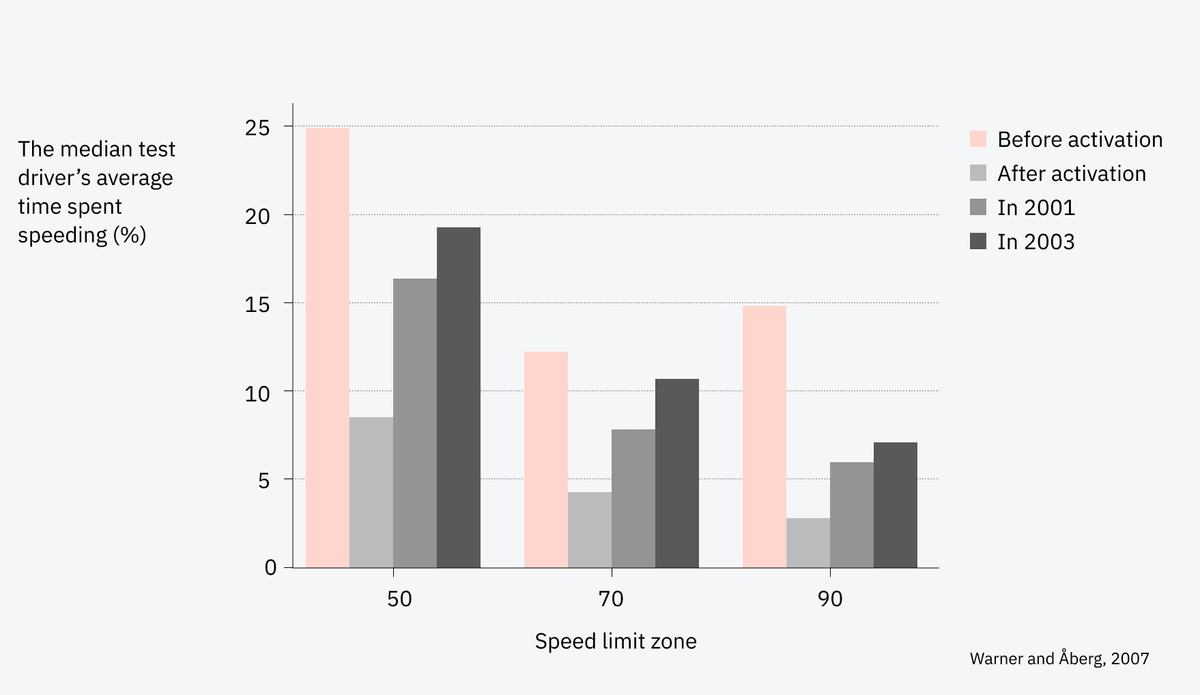

There was a spike in interest in ISA about 20 years ago. Around that time, several studies were conducted on a national level in different European countries and Australia. Most studies examine the effectiveness of the type of ISA — advisory, voluntary, or mandatory — and report the results as a difference in average speed, the difference in the time spent speeding, or a predicted reduction in fatality rate. The best research comes from Sweden where 4000 participants drove around with different types of ISA for a prolonged period.

Does ISA work?

Each of the three types of ISA work. Unsurprisingly, a mandatory ISA, the one that makes it impossible to speed, is by far the best with a potential fatal accident reduction of 30-60%. An advisory ISA, like the one currently implemented by most carmakers, is less effective but still has significantly positive results. In a trial in Australia, 89% of participants reduced speeding time with an advisory ISA. In the large Swedish study, drivers had a reduced average speed in all speed zones, with only minor differences between a mandatory and advisory ISA. Another Australian study with repeat speeders showed a significantly lower mean speed and a 40% reduction in time spent exceeding the speed limit when an advisory ISA was active.

There are positive side effects as well. Such as improved traffic flow, reduced emissions, and reduced societal costs and insurance premiums, all without a decrease in travel time.

There are some raised concerns with ISA. For example, when the alerts are perceived as annoying, drivers may turn them off, especially younger drivers. Perhaps a more important criticism is that the effect may diminish over time. The reduction in speeding is only there as long as the system is active. In other words, it does not result in deeper behavioral changes. That is not necessarily a problem as ISA is meant to be on all the time. However, over the long term, there is some indication that the results diminish. After the large-scale Swedish study, a small subset of drivers continued using a device with visual and auditory warning signals. Even though they still sped less time, the effect was smaller than during the initial study, gradually increasing every year after the study. This could be attributed to social control or getting habituated to the signals but more research is necessary to confirm this behavior and study the cause.

Driver acceptance

Most studies also researched public approval and they had positive results with the vast majority of drivers preferring some form of ISA. As expected, driver acceptance of a mandatory ISA is the lowest, while it is the highest for an advisory ISA.

One of the positive reasons stated is that people believe it makes them better drivers. Drivers liked to be aware of the speed limit, especially in lower speed zones, and some liked the fact that it reduced the number of times they had to look down at the speedometer.

Visual vs auditory cues

Most studies used either only a visual indicator, like a traffic sign that blinks when exceeding the limit, or a combination of visual and auditory signals. The goal of the studies is to test the type of ISA, not the interaction mode. There is no research on the difference in visual vs auditory cues in the context of ISA. However, there is some mention of it with regard to driver acceptance. Drivers clearly prefer visual rather than auditory queues. The reason being, among others, that the audio signal in the warning system was experienced as so irritating or distracting that attempts were made to avoid it.

In a broader context, the reason to choose an auditory signal over a visual one is that visual distraction is potentially worse than auditory distraction. The visual channel has a lot of bandwidth but also has to process a lot of information while driving. Any new visual information will compete with road and traffic information. As I've written in earlier articles about cognitive load and multi-tasking, it can help to spread information across modalities, but driver comfort must be taken into account.

On a cognitive level, auditory feedback arrives faster than visual feedback. That is why auditory cues are used when reaction time is important, such as in forward collision warning systems. However, the auditory channel does not have a lot of bandwidth and it is difficult for drivers to create a vocabulary of auditory signals. This is why it is easy to overload the driver resulting in stress. Most auditory warning signals come with a visual explanation to make sure the driver understands what is happening.

The EU proposes a 'cascading' warning, meaning a repetitive signal that increases in importance over time. There is no research on whether a repetitive signal works more effectively than a single signal.

More research is necessary to establish whether advisory ISA systems are time-critical enough to warrant an auditory signal on top of a visual one and whether a continuous warning is more effective than a single one.

Automotive cookie banner

It is undeniable that Intelligent Speed Assistance systems reduce speeding and therefore have the potential to reduce traffic deaths. But there is a discrepancy between the public acceptance in the studies on ISA and the systems that are in production vehicles today. This has everything to do with how the EU implemented its regulation.

The EU gives carmakers the illusion of choice between four different types of ISA because it's obvious that almost all carmakers will implement an auditory warning. Beeps are annoying and cause stress. This is fine if you want to warn of immediate impending doom that requires driver intervention. However, there is no evidence that an auditory signal is more effective in reducing speeding than a visual one. And there is no evidence that a repetitive signal is more effective than a single one.

It's therefore incomprehensible why the EU would enforce this implementation, especially when most cars have visual indicators already. The regulation has great intentions but the execution results in making the daily lives of millions of people just that little bit more annoying than it has to be. In a way, it is the automotive equivalent of cookie banners.

In fact, the European Transport Safety Council, one of the main proponents of ISA regulation, called on the European Commission to remove the need for an acoustic warning, stating the lack of evidence and negative user experience.

As a designer in the car industry, it's frustrating having to deal with this. I'd either remove the auditory signals and stick with a visual indicator, or let drivers turn the feature off permanently instead of turning it on by default. The one thing I can do is make sure that drivers can turn ISA off with one easy button press to avoid even more unnecessary distractions behind the wheel.

Get notified of new posts

Don't worry, I won't spam you with anything else